Here is my panel presentation for the ASAIK conference. Footnoting is a real problem in this form, so instead I’ve included a selected bibliography at the bottom. The piece is also liberally linked.

Here is my panel presentation for the ASAIK conference. Footnoting is a real problem in this form, so instead I’ve included a selected bibliography at the bottom. The piece is also liberally linked.

Presented by Marley Greiner

Edited by Erik L. Smith

Alliance for the Study of Adoption, Identity, and Kinship Conference

University of Tampa, November 19, 2005

““Stretch the paint, Todd. All we wish to do is put up a good front”

…..Arthur Kennedy to the handyman, A Summer Place (1959)

I have always been a big movie fan—especially of old films and maternal melodramas. After co-founding Bastard Nation in 1996 I began to seek out cinematic representations of bastards and adoptees. Although I grew up with Stella Dallas, Penny Serenade, Blossoms in the Dust, Shirley Temple, Disney, and the now impossible- to-find That Hagen Girl, I had never consciously identified with any of the characters nor with adoption narratives in general. But with a newly honed bastard consciousness I began investigating how Hollywood constructed cultural ideology and myths about us.

Out of the hundreds of adoption-themed films made, few examine the turmoil surroundng adoption as a social and political institution. Few take the adoptee point of view. Instead, most treat the adopteee as undeveloped, an object of desire/undesire. Adoptive parents, though often “heroic” are secondary characters, except when pursuing adoptive parenthood. Natural fathers are weak, ineffective, invisible, or dead. These textual silences are filled by the voice of the natural mother, whether she be passive victim or active agent of progress, or more likely something between the two. In real life, the natural mother is disempowered, disregarded and stigmatized. In film she is the star of her own narrative and, psychologically, a transgressive female heroine to her female audience.

Consequently, I had to investigate where bastards came from in film–the natural mother.

I focus here on two sub-genres of adoption film. After a brief introduction to the maternal melodrama, I will discuss selected The Fallen Woman films of the 1930s followed by selected Teen Sex films of the early 1960s. I will conclude by refuting the premise that Fallen Women and Teen Sex films represent a major shift in gendered film portrayal; instead the sub-genres uphold traditional ideologies of feminity, sexuality, and bourgeois family values.

Two reference points: (1 the natural mothers are sometimes married to the natural father, but due to class, connivance, or sham, are treated as though they are unwed mothers; (2) bastard means born out of wedlock or born in wedlock but to women isolated from the normative family for status reasons.

THE MATERNAL MELODRAMA

THE MATERNAL MELODRAMA

Traditional melodrama depicts morality with tension between realism and hyperbole. Plots deal with routine domestic life, but characters’ reactions and stylizations of events are extreme.Peter Brooks in his book The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama and the Mode of Excess, argues that melo “represents the theatrical impulse toward dramatization, heightening, expression, acting out.” The narrative form is confessional, with characters confronting each other over “true feelings,” though not always verbal. In Brooks’ words: the ”text of muteness” where words however unrepressed and pure…appear to be not wholly adequate to the representation of meanings and the melodrama message must be formulated through the registers of the sign.” Emotions can be so strong that only facial expressions, gestures, posture, moans, or cries—elements obviously inimical to the silent screen and later to the sophisticated style of full-blown family melodrama–can register them. Drama theorist John G. Caweti, carried Brooks further, stating: “melodrama texts make us feel that we have penetrated what shows on the surface to the inside story; it offers what appears to be the dirt beneath the rug”

Brooks and Cawelti argue that 19th century melodrama replaced the church as an on-going dialectic between good and evil since the narrative revolved around a moral dilemna. Gradually, however, the moral world moved away from the triumph of the virtuous individual via heavenly intervention and toward self-determination and earned success. But the conflict remained constant in structure: good v evil; virtue v corruption; heroism v villainy, with the moral order—in the case of the family—preserved from a largely external threat.

The maternal melodrama itself centers around a virtuous, but compromised, mother, who due to moral lapse, scandal, or circumstances beyond her control is compelled to believe that she must surrender the child to others (sometimes the natural father and his wife) for a proper and privileged upbringing. Separated from her child, and anonymous (usually the child doesn’t even know she has another mother), the banished mother watches from afar. In traditional maternal melodrama, the desire to be reunited with her child overrides all goals and ambitions, crushing her emotionally and often physically as well. In later versions, the mother usually loves the child but sees the child as a tool to gain reunion and marital happiness with the natural father.

THE 1930s: THE FALLEN WOMAN

THE 1930s: THE FALLEN WOMAN

Fallen Woman films sprang from 19th century European women’s domestic serials and novels full of tainted sex, corrupt aristocrats, seduction, and abandonment. The writers were mainstream: Hugo, Eliot, Collins, Trollope, Flaubert, and Zola. They portrayed female sexuality sympathetically, yet with the protagonist ultimately forced to pay for her sin with rejection, anonymity, or death. These elements appeared in earlier films, but for our purposes, American Fallen Woman films can be fixed with Frank Lloyd’s Madame X. (1920) followed by a later flock of weepies including Lummox (1930) East Lynne (1931), The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931), The Secret of Madame Blanche (1933) and Dorothy Arzner’s continent straddling, mixed genre Sarah and Son (1930).

“Madame X” followed the maternal melo formula: a woman banished from her domestic space, separated from her legitimate child, falling from her social class, and foundering in disgrace, while the child grows up respectably, enters society, and symbolizes progress and advancement. The fallen woman watches from afar for fear of contaminating the child’s fortunes with her ill repute. Chance eventually draws mother and grown child together, accomplishing partial or total rehabilitation of the mother–often through a courtroom scene. In the European tradition, the disgraced mother is punished and comes to an unhappy end, usually through prostitution, drug or alcohol addiction, or disease, her reunion and redemption too late. In American versions, however, happy endings are often tacked on which do not reflect the story’s basic pessimism.

French film critic Christian Viviani in the 1979 essay, ”Who Is Without Sin: The Maternal Melodrama In American Film 1930-39” establishes two lines of Madam X mothers and progeny: the Legitimate (Lego) in the European style where fallen women were submissive, resigned, sickly, naive, defenseless, indecisive, and the more interesting American Illegitimate (Bastard), where transgressive mothers rose from shady beginnings to redeem themselves through money, success and material culture. Living well was the best revenge.

Lea Jacobs in The Wages of Sin: Censorship and the Fallen Woman Film, 1928-1942, posited that the traditional Madame X, with its riches-to-rags depressed mothers and seduced-and-abandoned servants held little interest for young urban post-war audiences liberated from the European tales of sordid sex amongst the aristocracy. The modern Madame X needed to be adapted to a society without aristocracy, where the ideal was represented by the petit bourgeoisie, as exemplified in D. W Griffith’s Way Down East conflict between the unwed mother and culture. The Americanized Madame X reflected a modernist secular ideology of consumerism, appealing to a Depression-era, materially oriented, and sexually loosened female.

The class rise of the American X turned the moralistic European X on her head. Transcending class, economics, and traditional stigma of unwed motherhood, the American X represented at least a superficial and occasionally genuine, independent, spunky feminist alternative to absinthe sipping and street walking. Clearly sin paid!

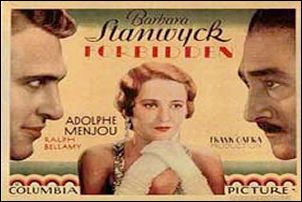

The first democratic melo was Henry King’s Stella Dallas (1925). The first important American X film, however, was Frank Capra’s Forbidden (1932) with Barbara Stanwyck creating the archetype of the energetic decisive and liberated heroine. This film was followed by John Stahl’s Only Yesterday (1933) featuring Margaret Sullivan as an unwed mother who chose anonymity by her own free will rather than respectable marriage with a man who forgot her, just as Ginger Rogers would do later in Kitty Foyle (1940). Setting the course for unwed mothers to follow, Sullivan found honorable work, and unlike her European counterparts, refused the life of a social outcast.

The first democratic melo was Henry King’s Stella Dallas (1925). The first important American X film, however, was Frank Capra’s Forbidden (1932) with Barbara Stanwyck creating the archetype of the energetic decisive and liberated heroine. This film was followed by John Stahl’s Only Yesterday (1933) featuring Margaret Sullivan as an unwed mother who chose anonymity by her own free will rather than respectable marriage with a man who forgot her, just as Ginger Rogers would do later in Kitty Foyle (1940). Setting the course for unwed mothers to follow, Sullivan found honorable work, and unlike her European counterparts, refused the life of a social outcast.

Menial work, popular in pre-1932 films like Lummox, was rejected by most X heroines unless it lead to a “good marriage” as in Common Clay (1930) and Private Number (1936) where female protagonists were maids for rich families with available sons.

The unwed mother, usually with working class origins, took up a profession. Barbara Stanwyck in Forbidden was a librarian and later a journalist with a couple of other professional jobs in between. Constance Bennett was a nurse in Born to Love (1931); Barbara Stanwyck a buyer in Always Goodbye (1938). Bette Davis and Ginger Rogers were secretaries in That Certain Woman (1937) and Kitty Foyle. Bette Davis ran an orphanage in The Old Maid (193)) and Ann Harding was a milliner in The Life of Vergie Winters (1934). Margaret Sullivan and Ann Harding were interior decorators in Only Yesterday, and its remake Gallant Lady (1933).

Ruth Chatterton, went from immigrant maid, to vaudeville star, to world-acclaimed opera singer in Sarah and Son; Kay Francis moved from small town theatricals to The Great White Way in Comet Over Broadway; and Mary Astor was a famous concert pianist in The Great Lie (1941).

The natural mother was played by a well-known lead. The second-banana natural father was seldom played by a name actor—at least at the time of release. He was weak-willed, vacillating, and wanted his family to make decisions for him. In Common Clay, he let his family treat Constance Bennett like a blackmailer; in Kitty Foyle he stood by silently while his family ordered Ginger Rogers, an adult in the workforce, to a finishing school. In Private Number, he let his parents push around Loretta Young and call her a gold digger. In That Certain Woman, Bette Davis and Henry Fonda were married only three hours when Fonda acquiesces to his wealthy father’s demand for an annulment.

The natural mother was played by a well-known lead. The second-banana natural father was seldom played by a name actor—at least at the time of release. He was weak-willed, vacillating, and wanted his family to make decisions for him. In Common Clay, he let his family treat Constance Bennett like a blackmailer; in Kitty Foyle he stood by silently while his family ordered Ginger Rogers, an adult in the workforce, to a finishing school. In Private Number, he let his parents push around Loretta Young and call her a gold digger. In That Certain Woman, Bette Davis and Henry Fonda were married only three hours when Fonda acquiesces to his wealthy father’s demand for an annulment.

The natural father was either emotionally or physically absent, missing in action, or dead. George Brent died in battle and was presumed dead in The Old Maid and The Great Lie. Nice guy John Boles, in Only Yesterday, was suicidal and didn’t recognize his former lover, Margaret Sullivan. In Born to Love, Constance Bennett’s lover supposedly died in the last days of World War 1. In Gallant Lady, Ann Harding’s fiancé was supposedly killed in the first reel.

The natural father was either overly attached to his mother in Wayward (1932), creating young mother/ old mother conflict, or committed to someone of his own social class as in Forbidden, That Certain Woman, and The Life of Vergie Winters. In Comet Over Broadway he was in jail. Occasionally, the natural father was a determined cad. In Sarah and Son, though married to the mother, he stole the baby, put it up for adoption, then joined the Marines.

Unlike her European counterpart, American Madame X films recognized the rights of the natural mother, albeit through a convoluted, incredible, or silly plot. The weapon used against her by the decadent oppositional family or culture was hypocrisy (Wayward, Private Number, Give Me Your Heart (1936), That Certain Woman, Kitty Foyle). In a cornball, but surprising, twist in Common Clay, natural mother Constance Bennett turned out to be a kept bastard whose natural father was hired by her lover’s father to ruin her reputation. In Sarah and Son, the wealthy adoptive Ashmores denied their son was Sarah’s and threatened to commit her to an insane asylum if she didn’t leave them alone.

Not all bastards were kept, but most were returned, by ruse or accident, by the end of the film After a long attempt at single parenting, the natural mother, unlike her European sister, voluntarily relinquished her child for a better life to a childless couple, often the natural father and his infertile or sickly wife. That Certain Woman contained an unintentionally hilarious encounter between natural mother, Bette Davis, and Anita Louise, the crippled wife of natural father Henry Fonda, in which each woman declared her eternal love for Fonda and demanded the other not only take the child, but Fonda as well!

Voluntary relinquishment no matter how painful however bears fruit. In Always Goodbye, and Gallant Lady, Barbara Stanwyck and Ann Harding, marry the adoptive fathers of their children after the adoptive mother dies. In That Certain Woman, Bette Davis and Henry Fonda reunite over their son in a phone call after Fonda’s wife is killed in a traffic accident.

In Only Yesterday, Margaret Sullivan meets John Boles years after the birth of their son, Butler, though she fails to inform him about his son. They fall into bed (Boles doesn’t recognize Sullivan as his long-ago lover) for another one night stand. At the end, Boles returns to Sullivan’s apartment, finds her dead from heart failure and learns that Butler is his son. In a touching closing, Boles tells Butler that he now has a father.

The reunion in Sarah and Son plays out a little differently. Sarah, played by Ruth Chatterton, while entertaining troops in a European military hospital, finds her runaway husband on his deathbed. With his last breath he whispers to her the name of their son’s new parents—Ashmore. After a convoluted story, in which Mrs. Ashmore’s brother, Howard Vanning (Frederic March) falls in love with Sarah, a reunion is facilitated between Sarah and son Bobby when he runs away from the Ashmores, meets up with Sarah and Vanning, and refuses to return to his “forever family.”

The pessimism of Forbidden is a glaring exception to the family reunion standard. In the final scene, Barbara Stanwyck tears up the will in which politician and long time lover Adolph Menjou declared her the mother of their daughter and guarantees them his fortune.

The pessimism of Forbidden is a glaring exception to the family reunion standard. In the final scene, Barbara Stanwyck tears up the will in which politician and long time lover Adolph Menjou declared her the mother of their daughter and guarantees them his fortune.

ODD COUPLES

Nearly all Fallen Woman film conceits are found in The Old Maid and The Great Lie. But these films contain a unique element: the mottled relationship between the natural and adoptive mother and baby, a wrangling far exceeding the husband banter in That Certain Woman.

The Old Maid, based on the Edith Wharton novel, stars Bette Davis as Charlotte Lovell, with her scene stealing studio rival Miriam Hopkins as Delia Lovell, cousins in love with the same man: gone missing ne’er-do-well Clem, played by George Brent. On the day of Delia’s marriage into a proper family (not Clem’s)—conveniently on the eve of the Civil War—Clem, returns to claim the bride for himself, but is rejected. On Delia’s wedding night, Charlotte, long suffering the torch for Clem, plays the comforter and ends up pregnant. By the middle of the first reel, Clem gets himself killed, leaving Charlotte to fend for herself. Determined to keep her baby, the secretly pregnant Charlotte fakes illness and hides in Arizona for a few years. When she eventually returns home, she passes off daughter Clementine (Tina) as an orphan and, as if to prove a devotion to child welfare, opens an orphanage in her home. When financial setbacks and illness force Charlotte to close the orphanage, and Delia accidently discovers Tina’s true proveance, Tina persuades Charlotte to let her adopt Tina. Eventually, the nurturing, vivacious Charlotte, who also moves into Delia’s home, turns into the Plain Jane old maid aunt, sexually guilty, and niggling Tina over nice girl behavior, convinced Tina will “go bad” just like she did.Played within the framework of antebellum soap, the heart of the film is the relationship amongst the cousins, the invisible Clem, and of course, his sacred child Tina. Rivals in love and in motherhood, the Charlotte and Delia forge an uneasy truce for Tina’s sake. Charlotte regretfully takes on the role of the crank and the nag, reviled and ridiculed for her old-fashioned ways and school marm appearance, the butt of Tina’s jokes—while she watches Dear Cousin Delia reap the benefits of Tina’s love and devotion.

The Old Maid, based on the Edith Wharton novel, stars Bette Davis as Charlotte Lovell, with her scene stealing studio rival Miriam Hopkins as Delia Lovell, cousins in love with the same man: gone missing ne’er-do-well Clem, played by George Brent. On the day of Delia’s marriage into a proper family (not Clem’s)—conveniently on the eve of the Civil War—Clem, returns to claim the bride for himself, but is rejected. On Delia’s wedding night, Charlotte, long suffering the torch for Clem, plays the comforter and ends up pregnant. By the middle of the first reel, Clem gets himself killed, leaving Charlotte to fend for herself. Determined to keep her baby, the secretly pregnant Charlotte fakes illness and hides in Arizona for a few years. When she eventually returns home, she passes off daughter Clementine (Tina) as an orphan and, as if to prove a devotion to child welfare, opens an orphanage in her home. When financial setbacks and illness force Charlotte to close the orphanage, and Delia accidently discovers Tina’s true proveance, Tina persuades Charlotte to let her adopt Tina. Eventually, the nurturing, vivacious Charlotte, who also moves into Delia’s home, turns into the Plain Jane old maid aunt, sexually guilty, and niggling Tina over nice girl behavior, convinced Tina will “go bad” just like she did.Played within the framework of antebellum soap, the heart of the film is the relationship amongst the cousins, the invisible Clem, and of course, his sacred child Tina. Rivals in love and in motherhood, the Charlotte and Delia forge an uneasy truce for Tina’s sake. Charlotte regretfully takes on the role of the crank and the nag, reviled and ridiculed for her old-fashioned ways and school marm appearance, the butt of Tina’s jokes—while she watches Dear Cousin Delia reap the benefits of Tina’s love and devotion.

Twenty years of resentment, deceit, and lies break open the night before Tina’s marriage to a wealthy local as Charlotte threatens to tell Tina the truth about her parentage. In the tense climax, Charlotte goes to Tina’s room to tell her the truth, while Delia stands on the steps fearful. With sudden Madame X clarity, Charlotte, realizes the revelation will only destroy Tina. Charlotte kisses her goodnight and joins Delia. By the end, the two make peace with themselves and the past, content they have co-mothered their daughter.

A not-so-tolerable and often disturbing relationship is explored in The Great Lie, a film that reverses the birth mother/adoptive mother stereotype. First wife/concert pianist Sandra Kovac (Mary Astor who won an Academy Award for the performance) and second wife/horsy set Maggie (Bette Davis) enter an ambiguous, symbiotic, and contentious relationship after their shared husband Peter Van Allen (George Brent) is reported missing in a plane crash in the Amazon.

Sandra, married to Peter during a night of heavy partying (the marriage obviously a nod to the Production Code and conveniently annulled when the couple learn that Sandra’s divorce from her first husband isn’t final) finds herself pregnant after their quickie divorce and his quicker marriage to true love, Maggie Patterson.

Career or motherhood? It seems never a real question for sophisticated Sandra who looks good in beaded dresses and has a personal hairdresser. Jealous of Sandra’s fertility, though having shown no previous penchant for motherhood, Maggie grabs the chance to take the baby off Sandra’s hands, turning from sophisticated, fun-loving debutante to greedy pap (potential adoptive parent). Maggie fakes her own pregnancy and spirits Sandra off to a shack in Arizona (again!) where the two play house with some deliciously bitchy dialogue written by Astor and Davis who found the original script impossible and embarassing. While Sandra is ambivalent about the pregnancy, Maggie attaches herself to the baby in utero, convinced God erroneously put “her” baby in Sandra’s tummy. Maggie, coyly yet aggressively concerned about Sandra’s health starts controlling her rival’s life—and body–demanding Sandra pay for her fertility and her fling with Peter.

Career or motherhood? It seems never a real question for sophisticated Sandra who looks good in beaded dresses and has a personal hairdresser. Jealous of Sandra’s fertility, though having shown no previous penchant for motherhood, Maggie grabs the chance to take the baby off Sandra’s hands, turning from sophisticated, fun-loving debutante to greedy pap (potential adoptive parent). Maggie fakes her own pregnancy and spirits Sandra off to a shack in Arizona (again!) where the two play house with some deliciously bitchy dialogue written by Astor and Davis who found the original script impossible and embarassing. While Sandra is ambivalent about the pregnancy, Maggie attaches herself to the baby in utero, convinced God erroneously put “her” baby in Sandra’s tummy. Maggie, coyly yet aggressively concerned about Sandra’s health starts controlling her rival’s life—and body–demanding Sandra pay for her fertility and her fling with Peter.

No drinking.

No smoking.

No onions.

And plenty of vitamins.

After one particularly unpleasant attempt to force Sandra to comply with her prissy regimen, Maggie slugs Sandra in the face. Sandra, who likes to call herself a “healthy woman with a healthy appetite,” (in more than one way, she suggests) retaliates by slouching around in a terrycloth bathrobe, smashing records, just wanting the whole miserable business over with.

After the birth, Maggie returns home with “her” baby, whom she promptly deifies as Peter Van Allen Jr. Sandra goes on an overseas tour. Both women are determined not only avoid each other, but to ensure that no one, not even the baby, will ever know the truth. But as melo would have it, the missing Van Allen, Sr. is mysteriously recovered from the Amazon and returns to Maggie and his new son, dumb to what has transpired between his wives. So dumb, in fact, that he is eager for the ménage to pal around together. The climax comes when Sandra visits the Van Allens for the weekend, planning to out Maggie and snag Peter for herself though the baby. In some touching scenes, Sandra emotionally connects with her son for the first time, especially when she learns that he has an ear for music, as Maggie frets, eye-rolls, and whines over the pending loss of her illegitimate family. At the last minute, Sandra marches the Madame X higih road. Watching Maggie, Peter, and the baby together, she announces she must return to the city; thus sacrificing happiness and mother love for her son’s future with the only family he knows.

THE 1960s: TEEN SEX

THE 1960s: TEEN SEX

Earlier films such as Elmer Clifton/Ida Lupino’s neo-realistic Not Wanted (1949) gave a hard-edged look at teen pregnancy and maternity home life, but not until the mid-late 1950s did Hollywood’s emphasis on the noble, sacrificing and respectable fallen woman take a turn south and begin to explore teen sex—a sure money-maker in the midst of the mid-century teen rumble. Films such as Rebel Without A Cause (1955) Splendor in the Grass (1959) All Fall Down (1962), A Summer Place (1959), Blue Denim (1962) The Young Lovers (1964) and the classic Ed Wood script The Violent Years (1956) were a far cry from Fallen Woman films, not to mention earlier “youth” films like Henry Aldrich Gets Glamour (1943), Love Laughs at Andy Hardy (1946), and A Date with Judy (1948). Peyton Place (1957) carried a triple whammy: The stepfather rape, impregnation, and illegal abortion of Selena Cross; the bastardy of Allison MacKenzie; and the issues of Allison’s mother who moved from noble Fallen Woman to an angry, sexually repressed successful business woman who, like Charlotte Lovell, wants to find her slut gene in Allison as much as she wants to keep her past secret from her daughter and the town.

Two films particularly broke ground exploring teen pregnancy. With stomach-churning precision, Blue Denim and A Summer Place depicted the consequences to “good girls” who transgress middle class sexual mores in the name of love.

Blue Denim is an important, though flawed, portrayal of teenage sexuality, a subject previously taboo in Hollywood which had portrayed sexually active women as those who knew the score.

Blue Denim is an important, though flawed, portrayal of teenage sexuality, a subject previously taboo in Hollywood which had portrayed sexually active women as those who knew the score.

Based on James Leo Herlihy’s hit Broadway play, Blue Denim tried an honest and sensitive portrayal of teenage sexuality, pregnancy and family dysfunction through Arthur (Brandon DeWilde) and Janet (Carol Lynley) who found themselves “in trouble” after their first and only sexual encounter. The play was hard-hitting and controversial, but the illegal abortion ending was too hot for Hollywood. Blue Denim was toned down, much to the dismay of even conservative Catholic critics who complained that Arthur and Janet’s compulsory marriage should never have happened. A reviewer for the Catholic Legion of Decency was so unhappy with the ending he insisted Janet should have been allowed to reject the shotgun marriage, but keep the baby and to grow into a mature relationship with Arthur.

A Summer Place, the penultimate dirty movie for a generation of high school girls, is full-blown melo, featuring family secrets, illicit sex, repressed sexuality, and alcoholism all exposed in public scandal. The plot centers on nice girl Molly Jorgenson (Sandra Dee) and her summer romance in Maine with clean-cut Johnny Hunter (Troy Donohue). Molly is sexually precocious but clearly a virgin (with a disturbing habit of chatting up her dad while wearing nothing but baby doll pajamas). Johnny vacillates between wanting to sleep with Molly and putting her off. Only a few days into the vacation, Molly and Johnny take an afternoon boat exursion, get caught in a storm that forces them to spend the night on an island. When the Coast Guard brings them home the next morning Molly’s man-hating monster mother (Constance Ford) obsessed with Molly’s virginity, her own dirty thoughts, and social status, sends for a doctor to make sure Molly is still in tact. The forced and degrading gynochologial exam, which Martha Mays rightly calls “maternal rape,” is one of the most chilling scenes in teen film, with Molly wrapped in a blanket pleading, “I haven’t done anything wrong. I’m a good girl.”

A Summer Place, the penultimate dirty movie for a generation of high school girls, is full-blown melo, featuring family secrets, illicit sex, repressed sexuality, and alcoholism all exposed in public scandal. The plot centers on nice girl Molly Jorgenson (Sandra Dee) and her summer romance in Maine with clean-cut Johnny Hunter (Troy Donohue). Molly is sexually precocious but clearly a virgin (with a disturbing habit of chatting up her dad while wearing nothing but baby doll pajamas). Johnny vacillates between wanting to sleep with Molly and putting her off. Only a few days into the vacation, Molly and Johnny take an afternoon boat exursion, get caught in a storm that forces them to spend the night on an island. When the Coast Guard brings them home the next morning Molly’s man-hating monster mother (Constance Ford) obsessed with Molly’s virginity, her own dirty thoughts, and social status, sends for a doctor to make sure Molly is still in tact. The forced and degrading gynochologial exam, which Martha Mays rightly calls “maternal rape,” is one of the most chilling scenes in teen film, with Molly wrapped in a blanket pleading, “I haven’t done anything wrong. I’m a good girl.”

Eventually Molly becomes pregnant by Johnny. At the end, the married Molly and Johnny, mentored by Molly’s father (Richard Egan) and Johnny’s mother (Dorothy McGuire), former teenage lovers themselves who have left their respective abusive spouses and are now married to each other, are seen arriving at the island where they first met, holding hands, untroubled by being totally unprepared for marriage–much less parenthood.

CONCLUSION

The maternal melodrama of the 1930s introduced a so-called progressive portrayal of American unwed motherhood. A closer look at the European and American Madam X, however, shows little difference between the Legos and the Bastards outside of some innovative tale-telling. lively acting, and an occasional feminist message in the American line. With the exception of Forbidden and the rebellious final act of Barbara Stanwyck, unwed mothers remain victimized by their families, the fathers of their children, and society at large. But more important, by themselves. Unlike European Madame Xs who are forced to give up their children through social pressure or very real coercion, American Xs after giving it the old college try, voluntarily relinquish their rights to the child; thus making them not only victims of economic, family, and societal pressure, but of their own self-delusion and ultimately their other-directedness. Their “choice” then is seen as an individual “responsible” decision, not a product of historical social force. While they may show a spunky independent front, the desirable natural father is never far from their minds. Unlike their European sisters who walk the gutter and are emotionally destroyed by the loss of their children, the American line actively schemes (or at last dreams) of ways to reunite with father and child and use the child (whether still with her or in the natural father/sickly wife environment), as an instrument to regain the loss.

Christian Viviani theorized that the cinematic unwed mother was set up as the antagonist to a “hoarding, speculating society—the repository of false and outworn values.” With her bastard, she symbolized the product of a decadent order and the hope of a better system, one based in the Protestant Work Ethic—dedication without promise of immediate compensation. While Madame Xs’s bastard child traditionally stood for progress and advancement, Viviani’s idea that they were a sort of a New Deal project, I believe is off the mark. Contemporary critics and social commentators in the 1930s, in fact were vocal in their condemnation of the underlying success message of the films, arguing that the films encouraged promiscuity or at least bad behavior on the part of women, but with little evidence to prove their case. It was probably the film’s success motif –a updated Cinderella story–that actually made the films popular, especially with working class women.

Blue Denim and A Summer Place were also considered progressive for their day. A Summer Place, especially, seemed to imply that teen sex was normal and to be expected. A closer reading of these films and others like The Young Lovers, where illegal abortion is rejected and balloons gently float skyward at the end, suggests a contrary and reactionary message quite different from the preceding decades. Teen sex maybe a fact, but the wages of sex is marriage. Unlike their predecessors, these films, though ostensibly more understanding and liberal suggest that proper sexual relations will occur only within the bourgeoisie marriage bed. Bastardy (or abortion) will not be tolerated. While “nice kids” Arthur, Janet, Molly, Johnny, superficially represent a turn from post-war conservatism, they are simply cautionary tales of youth and its consequenes. One expects to see this unhappy foursome a few years down the road, trapped in group therapy sessions after a day at some low-end job. Arthur and Johnny will eventually chuck it all for the Summer of Love. Janet and Molly will collect ADC and food stamps, start keypunch school and wonder what they ever saw in those guys other than their cute dimples and blond surfer looks.

Blue Denim and A Summer Place were also considered progressive for their day. A Summer Place, especially, seemed to imply that teen sex was normal and to be expected. A closer reading of these films and others like The Young Lovers, where illegal abortion is rejected and balloons gently float skyward at the end, suggests a contrary and reactionary message quite different from the preceding decades. Teen sex maybe a fact, but the wages of sex is marriage. Unlike their predecessors, these films, though ostensibly more understanding and liberal suggest that proper sexual relations will occur only within the bourgeoisie marriage bed. Bastardy (or abortion) will not be tolerated. While “nice kids” Arthur, Janet, Molly, Johnny, superficially represent a turn from post-war conservatism, they are simply cautionary tales of youth and its consequenes. One expects to see this unhappy foursome a few years down the road, trapped in group therapy sessions after a day at some low-end job. Arthur and Johnny will eventually chuck it all for the Summer of Love. Janet and Molly will collect ADC and food stamps, start keypunch school and wonder what they ever saw in those guys other than their cute dimples and blond surfer looks.

These films bring up questions that are worth further study:

(1) As Professor Wayne Carp suggested to me yesterday did Fallen Woman films create a paradigm for unwed pregnant women and unwed mothers or did the real-life women create the paradigm? That is, did the films influence the way unwed mothers viewed themselves and their decisions, or did the films reflect in any way the social and economic reality of real-life unwed mothers?

(2) Nearly all Fallen Woman and Teen Sex films were produced by male-dominated Hollywood despite Dorothy Arzner and Ida Lupino and the presence of strong women screen writers such as Zoe Akins, Frances Marion, Jane Murfin, Faith Baldwin, and Lillian Day. Is this male construction of “fallen womanhood” identity even valid or simply an outsider view of female identity?

(3) Fallen Woman films were produced not only during the golden Age of Hollywood, but the Golden Age of Hollywood Adoption with numerous big name stars including Ruby Keeler, Al Jolson, Dick Powell, Edward G. Robinson, George Burns and Gracie Allen, Bob Hope, Jack Benny Wallace Berry, Bette Davis and Joan Crawford for instance, adopting from places like the Cradle and Georgia Tann’s Tennessee Children’s Home Society baby mill. How then, were Fallen Woman and other adoption films influenced by the adoption friendly Hollywood environment?

Both sub-genres—the Fallen Woman and Teen Sex films—nudged the portrayal of female sexuality into more realistic territory and reflected in melodramatic terms a growing awareness or even acceptance of sexual behavior outside of normal marriage routines. The final message, though, continued to caution women to remain within the bounds of traditional bourgieous feminity, family, and behavior. As that other icon of feminity of the 1960s, Gidget learned:

Nice girls go on a date, go to bed, and go home.

Good girls go out on a date, go home, and go to bed.

_____

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brooks, Peter. The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama and the Mode of Excess. New York: Columbia University Press, 1981.

Browne, Nick. “Griffith’s Family Discourse: Griffith and Freud” in Christine Gledhill, ed. Home is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and Woman’s Film, London” British Film Institute, 1987.

Cawelti, John G. Adventure, Mystery and Romance: Formula Stories as Art and Pop Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976.

Considine, David M. The Cinema of Adolescence. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1985.

Doane, Mary Ann. “Time and Desire in the Women’s Film.” Cinema Journal 23 (Spring 1984).

Jacobs, Lea. The Wages of Sin: Censorship and the Fallen Woman Film, 1928-1942. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Jacobs, Lou. The Rise of the American Film: A Critical History. New York: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1939.

Kaplan, E. Ann. “Mothering, Feminism and Representation: The Maternal in Melodrama and the Woman’s Film, 1910-1940” in Christine Gledhill, ed., Home is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and Woman’s Film. London: British Film Institute, 1987.

Kuhn, Annette, ed. Queen of the B’s: Ida Lupino Behind the Camera. New York: Praeger, 1995.

Leibman, Nina C. Living Room Lectures: The Fifties Family in Film and Television. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995.

Mayne, Judith. Directed by Dorothy Arzner. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Peiss, Kathy. Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986.

David N. Rodowick, “Madness, Authority, and Ideology: The Domestic Melodrama of the 1950s ” in Chrsitine Gledhill, ed. Home is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and Woman’s Film, (London: British Film Institute, 1987..

Schatz, Thomas. Hollywood Genres: Formulas, Filmaking, and the Studio System. New York: Random House, 1981.

Simmon, Scott, The Films of D .W. Griffith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Vieira, Mark A. Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood.New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999.

Viviani, Christian. “Who is Without Sin?” The Maternal Melodrama in American Film” in Christine Gledhill, ed, Home is Where the Heart is: Studies in Melodrama of the 1950s. London: British Film Institute., 1987.

“Movies” aside, don’t you think it is just plain stupidity on the woman’s part to have gotten knocked-up post-birth-control pill? I mean, what kind of idiot female would have sex without protection? I’m NOT male either, but I was smart enough not to screw around without protection. You may defend “birth mothers” all you wish, but most people can’t ignore the “idiot” factor when birth control is readily available. (And it has been since the bp was made available.)

No, no, and no. The birth control pill is effective in preventing pregnancy, yes, but carries many health risks for women and also doesn’t prevent any of the myriad sexually transmitted diseases one can contract at present.

So it is by no means “plain stupidity” when a woman gets pregnant due to failed contraception, as I have more than once. I got pregnant while using a cervical cap, and another time when a condom broke, and I am far from stupid, thank you very much