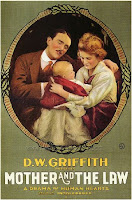

I’ve run short of time today, so to keep up the pace I’m posing here part of my study of adoption in film. This is first part of my longerl Where We Came From that I presented at the ASAC conference in Tampa in 2005, though this part was not included in the final draft. It stands on it’s own, though, there is much more to say about Griffith’s “bastard/adoption” work.

I’ve run short of time today, so to keep up the pace I’m posing here part of my study of adoption in film. This is first part of my longerl Where We Came From that I presented at the ASAC conference in Tampa in 2005, though this part was not included in the final draft. It stands on it’s own, though, there is much more to say about Griffith’s “bastard/adoption” work.

While the Cult of True Womanhood, with its Rousseau-like view of female piety, purity, domesticity and submissiveness, was still widely sanctioned in the US prior to World War I, Griffith’s early Biograph maternal melodramas were excessive for his era, and became more so as time went on.

While the Cult of True Womanhood, with its Rousseau-like view of female piety, purity, domesticity and submissiveness, was still widely sanctioned in the US prior to World War I, Griffith’s early Biograph maternal melodramas were excessive for his era, and became more so as time went on.

Very fascinating, something I’ve just begun to ponder and you answered some of my questions, thanks.

What a nice guy and so quick on his feet!

Thanks, Bastardette. This was fascinating! I can’t imagine where I would have seen any of these old films, except the famous ice floe scene, but the themes and the old maid social worker stereotype are very familiar. Didn’t this carry through to some Shirley Temple films and others in the 30s and 40s?

Too bad I did not remember them and take them seriously when being “counseled” about my unwed pregnancy!

I do remember thinking my social worker was among the ugliest women I ever saw, plus her eye twitched, and idly wondering if she had ever gotten laid. But still, I listened to her “expert” advice:-(

I love film. If I’d known that film was actually a “discipline” when I was in college, I’d end up a filmmaker.

There is so much work on Griffith, but I’ve never seen anyone write about adoption and bastardy. Unfortunately, much of his early work is gone and we can only read about it. If I had the time, I’d like to look into it more.

Shirley Temple films are full of the mean uplifter. There’s hardly a film she made without one. Captain January comes to mind, but of course, she’s won over. Little Rascals shorts have them. I especially like the one about the orphan train. And then there’s just plain old orphanages in films. When I was growing up I thought orphanages were all in haunted houses. And Jane Eyre doesn’t help.

Finally, I’ve seen 2 Madame X films this year that I’d not seen before. (Don’t have the titles right off hand), and following the American pattern (opposed to the European) they portrayed women down on their luck, forced to surrender their babies after trying to raise them on their own, who do in fact, return as mature successful women. One falls seamlessly into her son’s life, the other—hmm, gets executed (in the style of the French) for a murder she didn’t commit, prosecuted by the unwitting son the mother doesn’t want to shame.

The other film was a great bastard film I want to write about later. I saw it on TCM at 5 AM. It’s the pure bastard moment, which turns out OK (sorta) in the end. Nothing like marrying your bmother’s stepdaughter.